Yazeed Aldughaither

Editor-in-Chief

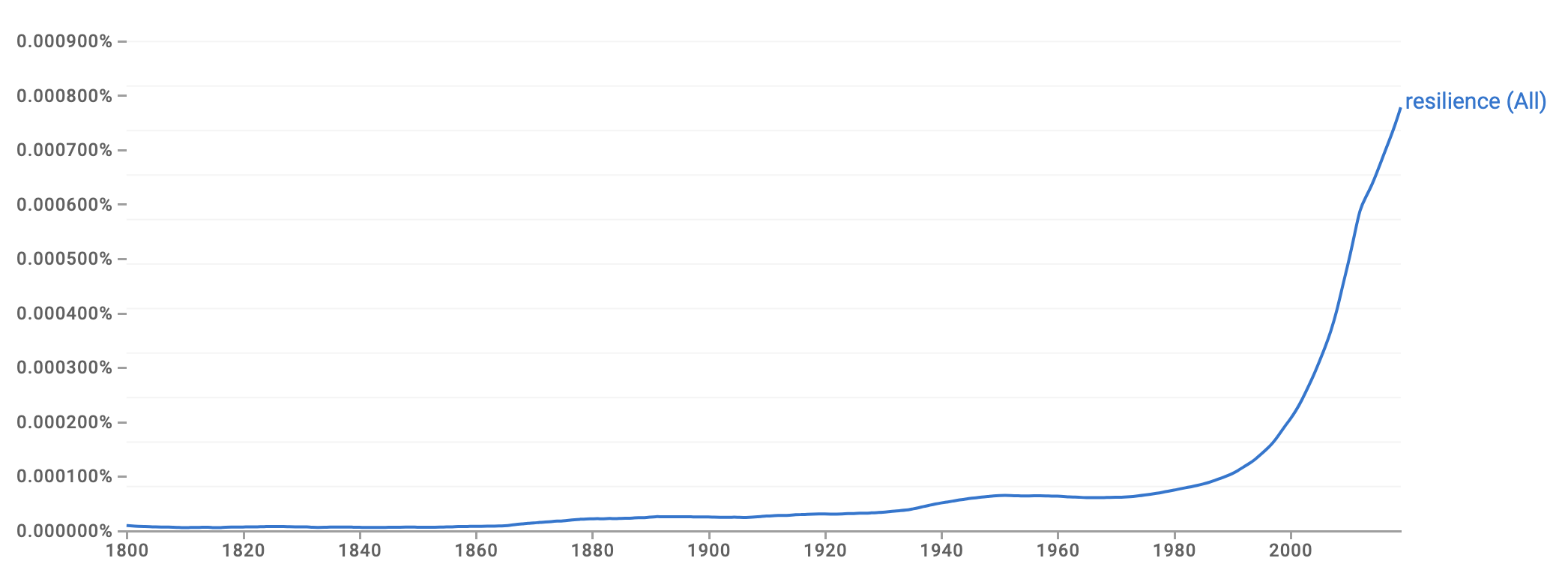

The notion of resilience has become one of the buzzwords of the moment, and can be heard anywhere from the boardrooms of the world’s largest companies, read in the pages of a self-help book, or uttered in fleeting conversations. While the concept may be one with which most of us are familiar, it may be worth exploring what that word really means in today’s fast-paced world, and whether that meaning has shifted across generations. Despite the still-growing frequency of its use, day-to-day conversations will demonstrate the fact that this concept is understood differently between different people and cultures. This is an especially pertinent issue for young professionals entering the workforce and facing a slew of novel challenges in an unfamiliar environment, and more specifically an environment which calls their own resilience into question.

Google Ngram showing the exponential increase in frequency of use of the term ‘resilience’ in writing in the last 20 years

Figure 1

While there are diverse opinions around what personal resilience might look like in the modern era, there is a general consensus that it is the quality of recovering quickly from setbacks. Resilience is therefore distinct from simple strength or perseverance, since the concept inherently acknowledges that all of us will eventually encounter challenges that will throw us off our balance, if only momentarily. Although it is commonly associated with toughness or tenacity, there is an undeniable element of flexibility and adaptability which is required to bounce back from these difficulties. It is this unique juxtaposition of two seemingly opposing notions (strength and flexibility) that forms the concept of resilience.

Some modern behavioral experts have also taken the concept of resilience a step further, and have coined the term “anti-fragility”, sometimes referred to as “resilience 2.0”. This comparatively novel concept of anti-fragility builds upon the preexisting foundation of resilience, and adds to it the idea that one can not only recover from setbacks quickly, but also do so in a manner that generates additional strength and learning that further fortifies that individual from future threats.

In fact, there are several examples of anti-fragile systems in natural and business worlds. The muscular system is one such example from biology: when we exercise, this results in microscopic tears in our muscle fibers. As our body recovers, it not only repairs those microscopically damaged fibers, it also creates stronger and bigger ones which are capable of withstanding loads greater than the ones that damaged them in the first place.

Another example is the global banking system, which tends to recover from near-catastrophic events (such as the 2008 crisis) in a manner that not only returns to baseline, but also results in a system that is less susceptible to the original risk factors that caused the crisis in the first place (e.g. subprime mortgages and ensuing securitization).

A final example comes from the world of psychology in the form of Post-traumatic Growth (PTG), a condition in which someone who faced a traumatic event later reports a greater appreciation of life, more meaningful relationships, and spiritual development.

With that being said, this raises several questions: can resilience be measured or actively cultivated? Or is it an intrinsic trait which can’t be acquired? The truth, as often is the case, is a complicated and non-binary answer that lies somewhere between nature and nurture. Consensus among leading behavioral experts suggests that resilience and anti-fragility, much like happiness, are best attained through indirect pursuit.

In other words, resilience is a byproduct and not an end result unto itself. A review of the literature reveals that this trait is a function of genetics, personal experiences (especially in childhood), and an individual’s current environment and context.

While this shows that resilience may not always be actively developed, it is nonetheless, at least in part, a byproduct of the process of living a balanced life. Such a life would incorporate both challenges and ease, and would honor multiple facets of a well-adjusted existence, as often represented by the SPIRE model.

In this context, the term SPIRE is an acronym which stands for the following components: spiritual, physical, intellectual, relational, and emotional. In fact, studies have shown that the number one predictor of happiness is spending quality time with our loved ones, which extends to the observation that the quality of our relationships is actually one of the primary predictors of anti-fragility. In the words of Dr. Bessel van der Kolk, professor of psychology at the Boston University School of Medicine: “How loved you felt as a child is a great predictor of how you manage all kinds of difficult situations later in life.”

Components of resilience (Source: Positive Psychology)

Figure 2

Understanding that the relational aspect is only one component of the SPIRE model also indicates that the problem is often not an excess of stress, but rather a lack of recovery. Other components, such as the spiritual component, also provide individuals with a northstar, or a sense of purpose. It is this sense of direction and calling that motivates us to get back up once we are knocked down, which we inevitably will be throughout the course of our lives.

With that being said, our lives are in many ways starkly contrasting with those of generations past such as our parents and grandparents. At this point, the vast majority of young adults and professionals have been confronted with the accusation from our elders of being entitled, undisciplined, selfish, and fragile. While it is undeniable that we enjoy a host of benefits across multiple domains including technology and social justice that prior generations worked hard to realize, it is also true that we are facing challenges that are novel not only to us, but to any generation currently alive.

Although the global economy has grown substantially in size, there is a notable transfer of wealth from younger generations to older generations in the last 20 years. Not only that, but inflation-adjusted purchasing power has also decreased for the current youth, where in many developed countries, the cost of purchasing an average home as a function of median average income has tripled over the course of a single generation.

Before even thinking of buying a house or getting a job, the current generation also faces increased competition when it comes to acquiring acceptances from institutions of higher education, where acceptance rates at top-tier universities in the US have plummeted sharply in the last two decades. While the younger workforce is comparatively higher-skilled compared to the outgoing generation, this also comes at the cost of increased expectations and workloads in many cases, with digital technology blurring the lines between work and homelife more than ever before.

These adversities coupled with some of the more insidious side effects of social media have led to a variety of mental health difficulties with anxiety and depression rates on the rise among the younger population. Even the most successful members of today’s youth are not impervious to these pitfalls, or other less severe but nonetheless trying and prevalent issues such as imposter syndrome.

Considering these struggles, it is clear that the road to resilience is not paved with a one-size-fits-all approach. While strength, perseverance, grit, and discipline are undeniable components of resilience, it is equally important to acknowledge that flexibility, pragmatism, critical thinking, and in some cases disruptive non-conformity are also part and parcel of resilience.

Dr. Steven M. Southwick, professor emeritus of psychology, PTSD, and resilience at Yale University offers a helpful observation: “Many, many resilient people learn to carefully accept what they can’t change about a situation and then ask themselves what they can actually change”. Bearing this in mind, I’d like to share some key takeaways for those of you intent on cultivating your own resilience:

- Understand that resilience is not exclusively an internal trait, but is largely influenced by the quality of your personal relationships. Few people go far without a strong social support system.

- Connect with your sense of purpose – in order to recover, it helps to understand your north star, which is connected to your goals, morals, and often your spirituality. Resilient people tend to be connected to something larger than themselves.

- Discern between what you can and cannot change or influence, and focus your energy on the former.

- Welcome challenges and adversity and accept that many of our limitations are self-imposed. This should be balanced with sufficient recovery time to prevent burnout or breakdowns.

- Remember that there is strength in vulnerability, lessons in defeats, and growth in adversity.

While the current generation of youth may enjoy both benefits and struggles that our forebears have not experienced, creating a better life for incoming generations is arguably the most noble and important calling of our productive years. With that, I would like to leave you with an excerpt from President Theodore Roosevelt’s now famous man in the arena speech (originally delivered at the Sorbonne in Paris in 1910) as some fruit for thought:

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”