This article follows the author’s search for the lowest spot in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, based on historical records and corroborated by remote sensing.

Nicoli Garner, Saudi Aramco

“Next day we crossed the Sabkhat Mutti. We decided we must make a detour and cross these salt-flats near their head, otherwise the camels might become inextricably bogged, especially after the recent heavy rain. They would only have to sink in as far as their knees to be lost.”

– Wilfred Thesiger, Arabian Sands (1959)

Nicoli Garner standing on polygonal mud crack structures formed by gypsum precipitation in Jaub Depression.

One of many facets that attracts me to the field of geology is discovering the many literary and mapping works of our field’s geologic pioneers. While working as a geologist in Saudi Arabia, I was introduced to Arabian Sands by Wilfred Thesiger. After his arrival in Saudi Arabia in 1945, Thesiger spent several years living with Bedouin tribes, studying their way of life and culture. During his time in the region, Thesiger embarked on several challenging expeditions, including crossing the Empty Quarter, Rub’ al Khali Desert, which was an incredibly difficult and dangerous undertaking. His travels and experiences in the region were documented in his book, Arabian Sands.

I read Thesiger’s passages referencing geographic depressions, salt-flats, and quick sands in an area just south of the Qatar peninsula and was unequivocally convinced that I must follow Thesiger’s footsteps to find what is believed to be the lowest point in Saudi Arabia.

The lowest surface elevation within the Arabian Peninsula is located in the Jaub Depression, inland from Sabkhat Mutti. This location has been verified by digital elevation mapping, a hand-held GPS device, and field observations. The Jaub Depression was described by Thesiger in the accounts of his 1947-48 crossing of the Empty Quarter. We applied current geological knowledge, observations from historical records, surface mapping, and satellite imagery to retrace Thesiger’s steps, literally. This ultimately confirmed the elevation and developed insights into the origins of this closed basin below sea level. “A miserable camp-site in the Jaub (Depression). By now hunger, thirst and tiredness were a burden, and all depended on finding some water and grazing. Day after day there was nothing for the camels. Each morning I expected to find some of them dead… Those were bad days.” – Wilfred Thesiger, Arabian Sands (1959).

“A miserable camp-site in the Jaub (Depression). By now hunger, thirst and tiredness were a burden, and all depended on finding some water and grazing. Day after day there was nothing for the camels. Each morning I expected to find some of them dead… Those were bad days”

– Wilfred Thesiger, Arabian Sands (1959)

I was compelled to see this depression firsthand after reading Thesiger’s description of the area, and how his group came so close to dying during the crossing. Sabkhat Mutti was known to be just east of Highway 95, which passes through the northern section of the Empty Quarter (Rub’ al Khali) Desert. As a geologist, what I noticed when reading Thesiger’s account of his 1947-48 second crossing of the Empty Quarter was how he avoided the low points and salt flats as they were dangerous, soft, and sticky (inextricably bogged), especially since it was raining during his trip.

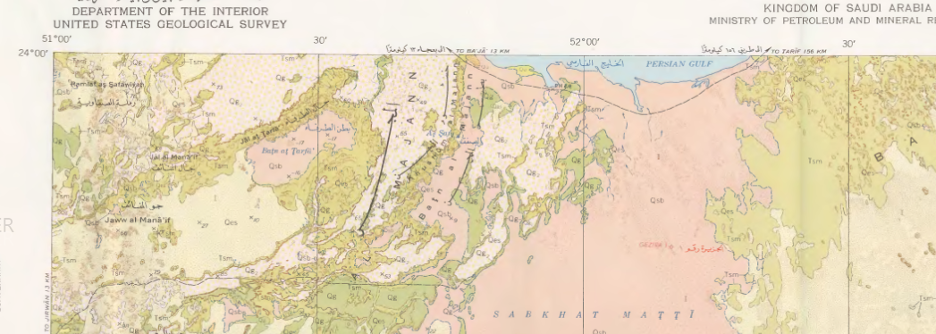

The early descriptions of this depression were recorded in Thesiger’s travel notes, but an explanation of the geological underpinning has not been presented until now. Similar depressions occur throughout the Central Arabian graben system, which formed as a result of Quaternary fault motions as identified by surface mapping conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in the early 1960s (Bramkamp et al., 1961). The extent of this faulting was underestimated because the tectonic features vanished under the alluvial gravels and aeolian sands eastward and were believed to be limited to the Awsat, Nisah and Sahba Grabens, south of Riyadh. However, this theory was revisited in the early 1980s and early 1990s when the Space Shuttle Imaging Radar (SIR) revealed a 250km lineament system below the extensive tertiary strata (Dabbagh et al. 1997). These lineaments connect the Nisah and Sahba fault systems with the 700km east–west oriented Trans-Arabian Gulf Fault System under the Arabian Gulf, together defining the southern edge of the Eastern Arabian Tectonic Block. Our analysis shows that the last landward expression of this extensive fault/lineament system is a 5km wide and 26km long basin known as the Jaub Depression as discussed in Thesiger’s notes. Thesiger had crossed nearly a century earlier as part of a field study for the British Government to determine the source of locust breeding grounds that plagued the eastern region of the Arabian Peninsula.

The lowest elevation within the Jaub Depression is located in the northeastern portion of the basin (23°50’54.65″N, 51°32’22.82″E) at a depth of 17.5 meters below sea level. Large portions of the basin are covered with wind-blown aeolian deposits, while the basin edges are marked by alluvial fan infill. The occurrence of numerous polygonal mud crack structures formed by gypsum is observed and attributed to the remnants of ephemeral lakes that identify the lowest drainage point in the basin. The large evaporitic “salt-flats” (gypsum and halite) polygonal crust was formidable to traverse in an air-conditioned off-road vehicle; I can see why Thesiger’s camels walked around this hazard.

Satellite imagery, digital elevation mapping, and hand-held GPS device enabled the rediscovery of this remote geomorphic feature, which was originally recorded by Thesiger: “We crossed some salt-flats to the far side of the Jabrin depression, my map showed only a single well called Dhiby, located at the end of his great journey across the Sands”.

“We crossed some salt-flats to the far side of the Jabrin depression, my map showed only a single well called Dhiby, located at the end of his great journey across the Sands.”

As you read the pages describing Thesiger’s difficulties in 1948 — walking through this same depression as part of a camel caravan led by Bedouin guides — you can trace the British explorer’s tracks across a satellite image, while protected from the heat in an air-conditioned off-road vehicle. How different the exploration approach was a century ago. The added level of safety and comfort provided by modern GPS systems, satellite phones, and protection from the harsh elements, does not make the Jaub Depression, the lowest point in Saudi Arabia, any less desolate. The location is still without water, sand still stretches out in all directions, and gypsum mud cracks pockmark the surface. Other than Highway 95 and the remnants of the Dhiby well, there is little to be found for 50 kilometers in any direction. While I can relate to the wonder that Thesiger must have experienced as he witnessed the sublime beauty of the Empty Quarter (Rub’ al Khali), I would never attempt to retrace his footsteps in the harsh desert environment without modern technology for navigation and comfort.

What a fascinating report! Thank you for sharing this.

You can review some wonderful photos of Thesiger’s Second Empty Quarter Journey from December 17, 1947 – March 14, 1948 archived by the Pitt Rivers Museum;

https://web.prm.ox.ac.uk/thesiger/index.php/thesigers-journeys/15-thesigers-journeys-in-arabia-second-empty-quarter-crossing-1947-8.html